Following the 1998 appearance of the London Jazz Composers Orchestra at the Berlin Jazz Festival, it seemed as if Barry Guy�s legendary large ensemble might, after some 25 years, be coming to an end. They certainly quieted, and before long the Barry Guy New Orchestra looked to be filling its role.

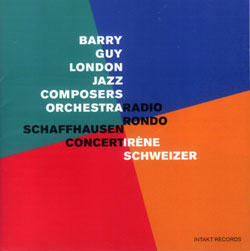

But a decade later, the orchestra returned 18 strong with pianist Irene Schweizer at the center at the Schaffhausen Jazzfestival in Switzerland, home to both Schweizer and Intakt, the label releasing this landmark set. Or two sets, in fact. Or perhaps an only partially intended suite, or a fantasia on beginnings, endings and possibilities.

It was the festival�s idea to have Schweizer play a short set before the full band, perhaps to fill out the slot before the roughly 30 minutes of Guy�s new composition. And whether or not it was her intention, Schweizer�s 15-minute solo feels like an improvised overture for the orchestral piece. It is elegant, virtuosic, and touches on Guy�s themes in nicely understated ways. The overture here, leads unconventionally to the rondo, which generally is the final movement in a sonata but in Guy�s case becomes the whole of it. It�s likely enough that the composer is using the word here purely for it�s alliterative strength; having played much classical music, Guy no doubt knows the term�s usage. But the title Radio Rondo contains intriguing implications. He makes clear in the liner notes that his intention was to simulate the scanning of a radio dial while incorporating the work that the orchestra�s members have done over the decade break. But is the orchestra�s new beginning an ending, or is it the end of radio itself that he is referencing? Certainly, broadcast radio listening is on the decline, and �tuning in� online doesn�t allow for the same scanning of stations. Thus the rondo becomes a fantasia. What if you could not scan the dial without hearing the LJCO? What if commercial media still supported jazz? What if a piano solo could still sell soap?

Suppositions about intention aside, Guy�s broad composition does carry something of the disjointed unpredictability of roaming the dial, although not in a Zorn fast-cut manner. It builds organically while remaining unpredictable, and is an awful lot (almost too much) to absorb. The who�s who includes Evan Parker, Mats Gustaffson, Trevor Watts, Conrad and Joseph Bauer, Herb Robertson, Phil Wachsmann, Barre Phillips, Paul Lytton and Lucas Niggli, an impressive array, and all are given interesting solo and small-group settings. It might

Comments and Feedback:

More Recent Reviews, Articles, and Interviews @ The Squid's Ear...

|