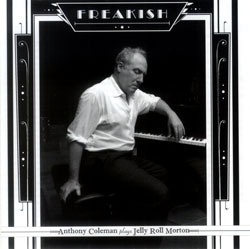

Ragtime has run an unusual road from the syncopated soundtrack in early 1900s brothels to the accelerated novelty tunes backing Benny Hill and The Sting to its current quasi-classical nostalgia. It's a pianist's showcase to be sure, but the showmanship is to be found in its angular swing, not a high-speed chase. Anthony Coleman, a walking encyclopedia of jazz history, knows well what's to be found and to be avoided in the rags of Jelly Roll Morton, as is well evidenced by his album collecting a dozen pieces (one presented twice) from the self-proclaimed inventor of jazz. Even down to the title, Freakish, Coleman shows he knows these are something more than good-time Charlie tunes.

Coleman eloquently writes in the liner notes that he is intrigued by "neither the idea of re-creation nor the idea of updating � taking works as a framework for wild interpolations." And such, succinctly put, is his mission here. He's savvy enough to find a place for himself within Morton's compositions without trying to wholly embody them. His playing is mostly straight, metered and mid-tempo, but within that there's glimmers of the contemporary player. The momentary pauses and slight tempo shifts he weaves into "Fickle Fay Creep," for example, may be subtle, however they make this not just another Morton record, but a significant one.

Coleman understands what many modern-day ragtime players miss, that while it's a more formal music than the jazz that would spring from it, it's not quite as restrictive as the parlor music that preceded it. Chopin and Saint Sa�ns may have left room for interpretation, but they didn't have the breakdown. Morton, Buddy Bolden, Scott Joplin and the New Orleans players were finding a new musical freedom. Coleman's notes aren't lengthy but they are illuminating (and connect sweepingly to Harold Bloom, Jorge Luis Borges and Miguel de Cervantes in ways that needn't be outlined here). He sees in the rags the presaging of bop and the dissolving that, once adapted to the saxophone, became that free blowing section, the spontaneous variation, the soloing at the heart of later jazz. Morton was "a conceptual thinker of a very particular order [Coleman writes], and he sacrifices surface color and excitement and contrast to his ideas about language. That is why his music will never engage as many people as Duke's or Armstrong's." The same could be said of Coleman and, added to both, that fortunately they don't let concept cloud the creation.

Comments and Feedback:

More Recent Reviews, Articles, and Interviews @ The Squid's Ear...

|