![Sun Ra Arkestra: Sunrise In Different Dimensions [VINYL 2 audiophile LPs + 4 postcards] (Hat Hut) Sun Ra Arkestra: Sunrise In Different Dimensions [VINYL 2 audiophile LPs + 4 postcards] (Hat Hut)](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/21191.jpg)

One of the exciting aspects of record store shopping in New York City in the 80s and 90s was going to the mezzanine section of Tower Records on 4th St and flipping through sections of non-commercial, remarkable albums from artists I barely or didn't know anything about. Standing out in that section were always a number of albums on the Hat Hut label from Switzerland. These were easy to spot as they were packaged as an LP box, with colorful artwork, holding post cards, liner notes, and images inside the the box. Artists like Anthony Braxton and John Zorn filled their catalog. These albums presented some of the most extreme creative artists of the time, and also presented themselves handsomely in my record collection.

Fast forward several decades and the Hat Hut label continues, now a recognizable and high quality CD label still issuing creative improvisation, new and in reissue, with a catalog that is desirable to listeners of straight-ahead jazz, avant jazz, avant classical, ea-improv, and much more. Their reissues have remastered and updated the music from the original LP releases, sometimes adding new material, and offering new perspectives to the original release. For Squidco it is one of our most interesting labels, and we're proud to be the US distributor for their releases.

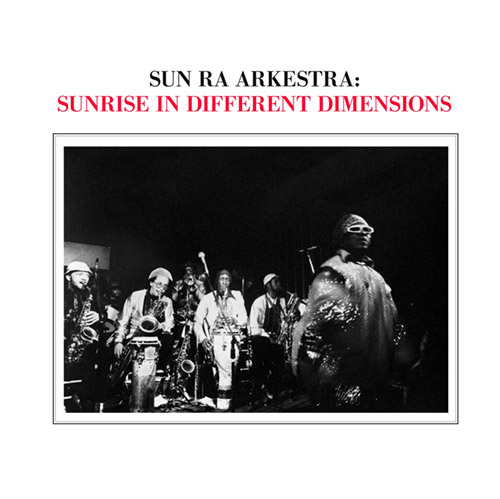

We're also enthusiastic Sun Ra fans, so we were thrilled to learn that Hat Hut is reissuing a seminal Sun Ra release on vinyl, Sunrise in Different Dimensions, in its original 2 LP edition, restoring 19 minutes of material that was removed from the remastered release to make it fit a single CD format. This new release is an audiophile quality vinyl issue.

Here's the new cover for the release:

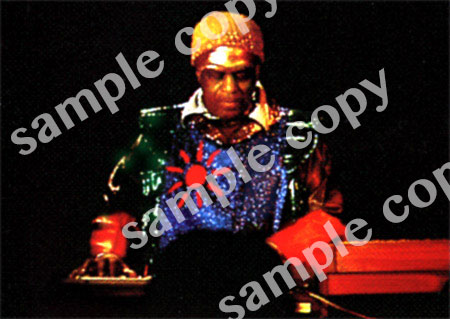

Here's an image of one of the postcards from the new release:

And last, here's the full release promotion:

“Beauty is necessary for survival.”

So Sun Ra told me in 1983.

Beauty certainly played a major part in his aesthetic from the outset. In his notes to the first Arkestra LP, 1957's Jazz by Sun Ra (reissued as Sun Song), he wrote: "All of my compositions are meant to depict happiness combined with beauty in a free manner." He also insisted that "every civilization is determined, to great extent, by the scope and development of its Art Forms . . . One of the decisions America must make is as to whether Music Is An Art or merely a commercial gimmick."

This dichotomy, between art and beauty on the one hand and commercialism on the other, seems to have been a consistent thread in Sun Ra's worldview (with the former often associated with originality and the spontaneous, the latter with imitation and the manufactured). But by 1989 the optimism that had infused the Sun Song liner-notes had given way to a more angry and frustrated response to America's and the world's attitude to beauty. Noting (in an interview with Mark Sinker) that "people who deal in physical things", such as football players and boxers, earn millions of dollars in America, Sun Ra

asked: "Why can't the world open its doors for those of us who have some beauty and art to offer open its doors and forget that we're so-called black or whatever? We're artists and we have beauty. And we need money to present it to the world. The world must not be doing to us like it did to Mozart . . . [that is] a terrible indictment on the planet. It's ridiculous to take an artist, to throw him down into a pauper's grave, to throw lime on top of him that is the most disgraceful thing I ever heard of."

This outrage on Mozart's behalf notwithstanding, Sun Ra's chief musical idol was Fletcher Henderson, with whom he worked at Chicago's Club DeLisa in 1946-47, though it was Henderson's orchestra of the late 1920s and early 1930s that he held in particular esteem. Indeed, in a 1970 interview with Tam Fiofori, Ra paid handsome tribute to all of the black bands from that period. "Some of the bands I heard never got popular and never made hit records but they were truly natural Black beauty . . . The music they played was a natural happiness of love, so rare I cannot explain it." Their lack of success, he suggested, was due to music being valued "as only a commercial commodity".

Commercialism was not the only force with which beauty had to contend. Ra's plea (above) for people to "forget that we're so-called black or whatever" indicates he was well aware that racism too could cause beauty to go unrecognised. And its creators to go unacknowledged. Ra believed that ancient Egypt, the world's first great civilisation, source of art and beauty, had been a black civilisation, though some white historians tried to deny it. He also believed the Church had used the Old Testament to trick African American slaves into identifying with Moses and the Israelites rather than with Pharaoh and the Egyptians, thus cutting them off from black history and denying them a source of pride in black achievement. So he tried to promote Egypt in his music, just as he paid tribute to artists like Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson, whose bands he saw as models of unity and creativity, and as the finest bloomings of 20th century black culture.

His description of those early bands as representing "Black beauty" recalls Duke Ellington's use of that phrase, as the title of a 1928 composition dedicated to singer and dancer Florence Mills, a Harlem favourite who had died suddenly the previous year. Ellington's title may seem innocuous today, yet 'Black Beauty' carried a potent charge of racial pride in the 1920s, when blackness was more commonly associated with ugliness. (At the Cotton Club, where Ellington was then working, the black female dancers had to be light-skinned in order to please the white clientele "nothing darker than a light olive tint," according to historian Jim Haskins.)

The white critic R.D. Darrell used 'Black Beauty' too, as the title of a 1932 article in which he praised Ellington as one of the most original and talented of modern composers. This essay marked the first serious critical appreciation of Ellington's music and, at a time when many Americans still regarded jazz as uncouth and barbarous, Darrell drily acknowledged that his was a minority view: "my neighbor sees only mud where I see gold, ludicrous eccentricity where I find an expressive expansion of the tonal palette, tawdry tunes instead of deep song, 'nigger music' instead of 'black beauty'." (Sadly, a large number of middle-class African Americans at the time would probably have agreed with Darrell's neighbour jazz was subject to class, as well as to racial, prejudice.)

There's a poignant irony in the fact that a similar set of prejudices have prevented some people from appreciating the beauty of Sun Ra's music though the prejudice here has often had less to do with the music per se than with the intellectual framework in which he presented it. Sun Ra's Astro Black Mythology influenced every aspect of his work, from song lyrics to LP sleeve designs to onstage movement and costume. Through its twin focus on outer space and ancient Egypt, it signified on, offered alternatives to and generally engaged with many of the topics and debates that have run through African American cultural history, making particular reference to Afro Baptist eschatology and conversion testimonies, 19th century spirituals and slave narratives, conflicting histories of Egypt and the writings of black intellectuals such as Martin Delany, W.E.B. DuBois and George G.M. James. Unfortunately these references went unrecognised by most white jazz critics, who failed to understand the intellectual context in which

Astro Black Mythology was operating (or even that it had an intellectual context) and mistook it simply for a bizarre and exotic spectacle. As a result, Ra was characterised as "a charlatan" and "a nutter", dismissed as "a circus act" and derided for his "tomfoolery" and "gobbledegook".

Such acts of cultural blindness are hardly infrequent. This is one reason why invisibility has been such a prominent theme in African American culture; as the narrator of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man explains: "I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me." Many black art forms have similarly been rendered invisible when viewed through white eyes yard art, for example, which, as John F. Szwed has observed, in breaking "from the European tradition of yard and garden is often read by whites as being no art at all, merely the untidy accumulation of junk". It seems the grandchildren of Darrell's neighbour continue to uphold the tradition of myopic prejudice, seeing junk instead of black art, gobbledegook instead of black philosophy. Or as Sun Ra put it in the opening lines to his poem 'Darkness Light':

Behold My House Of Light

Is Said To Be A House Of Darkness Because It Is Invisible

Sunrise in Different Dimensions comes from a 1980 Willisau concert. According to The Earthly Recordings of Sun Ra, an epic piece of research by Robert L. Campbell and Christopher Trent, this was the Arkestra's first date of a three-month European tour, which explains the curious line-up here (single trumpet, no trombones, no bass): Sun Ra had been expecting other band members to join him as the tour progressed. The advantage of this instrumentation is that Ra's piano is well to the fore, not only in a series of excellent solos but also filling in the bass role. Marshall Allen and John Gilmore, masters of all idioms, share the reed solos, their virtuosity evident from the spirited high-register conversation on 'Silhouettes of the Shadow World' to a range of solos on more traditional pieces check the passionate, volatile alto on 'Cocktails for Two', the adroit tenor bustling purposefully through 'Round Midnight'

The other main soloist is Michael Ray, whose shrill, excitable trumpet may be more of an acquired taste, though he does some sterling work here as a one-man brass section.

The first eight tracks on the CD come from the first set, the remaining seven from the second. Hat Hut's Werner X. Uehlinger has confirmed that the choice of material on the CD (and previous LP releases) was his, and that he decided to omit the better-known space-related compositions: "I wanted to have more from the Arkestra's playing of the old originals, as this had not been presented [on record] at this time." That last statement isn't strictly accurate. Ra had started to feature the "old originals" in his concerts in the mid-1970s and by the time Sunrise in Different Dimensions first appeared as a two-LP set in 1980 (Hat Hut 2R17), a smattering of them had already appeared on disc, albeit on hardto-find labels such as the Italian independent Horo (the Unity LP) and Sun Ra's own Saturn label (the Taking a Chance on Chances LP). But Sunrise certainly represents the first time so many Ellington and Henderson classics were featured on a single Ra release. ('Big John's Special', written by Fletcher's brother Horace, 'Yeah Man!', 'Queer Notions', 'Limehouse Blues' and 'King Porter Stomp' were all in the Henderson orchestra repertoire.)

Incidentally, Sun Ra's own music on the CD reminds us that, as a pioneer of the newer, freer forms of improvisation which developed in the 1960s, his concept of beauty did not stop with past glories but also embraced the present and looked to the future. To deny the value of such innovation was, as he noted, just a ploy "to keep the creators down" and so render invisible yet another facet of black creativity.

When Sun Ra told me beauty was necessary for survival, I assumed he was talking in general terms. But it seems he had something more specific in mind. In 1989, asked by Mark Sinker about his recent performances of Walt Disney songs, Ra explained: "I felt that America had not given proper status or proper honour to those who do something worthwhile . . . I'd been doing Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Basie first I did that. The black folks still asleep, they didn't help me with that. So then I decided to take the white race and honour their brothers, because they hadn't done it either. So I did George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and finally I did the Disney thing."

The point, he said, was to draw attention to those "who brought some beauty to the world" in order to persuade "the cosmic forces" not to destroy humanity, which they might otherwise do given the sorry state of the planet. "But if I put up Fletcher Henderson and Walt Disney," Ra declared, "it's a shield of beauty."

Well, sooner Ra's shield of beauty (presumably the "invisible shield" he referred to in a 1970 composition title) than Dubya's missile defence system I doubt the cosmic forces will take kindly to that. But whether or not you believe beauty is necessary for survival, you can be sure that you're holding a little piece of it in your hand right now.

And who knows but that, in different dimensions, Sun Ra speaks for you?

With thanks to Victor Schonfield, Mark Sinker and Chris Trent. Graham Lock's book, Blutopia: Visions of the Future and Revisions of the Past in the Work of Sun Ra, Duke Ellington, and Anthony Braxton, is published by Duke University Press.

Comments and Feedback:

|