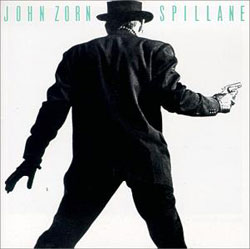

If 1985's The Big Gundown was the shot heard 'round the world for both John Zorn and New York's burgeoning downtown scene, then its follow-up, Spillane, was the revolution for real. The signal difference this time was that where the previous record had demonstrated the bold vision and commanding range of John Zorn's musical language as applied to western soundtrack compositions by Ennio Morricone, this time the compositions--and the vision--were Zorn's alone. Yet, from the very first line of his lengthy and revealing liner notes, Zorn challenges the assumption that the music contained therein could be solely attributed to him. "Whether we like it or not," Zorn says, "the era of the composer as

an autonomous musical mind has just about come to an end." Instead, Zorn cites the increasingly collaborative efforts of such disparate composers as Cage, Stockhausen, Ellington and Reich as being the touchstones of a more open approach to musical creativity.

Given the astonishing talent pool present in mid-'80s New York -- and in particular, early core collaborators Anthony Coleman, Bill Frisell, Wayne Horvitz and Bobby Previte -- who can blame Zorn for wanting to yoke their talents to his larger vision? And that's essentially exactly what he does on the titular composition, the first of his so-called "file card" compositions to achieve widespread circulation. (Its immediate predecessor, Godard, was originally available only on a hard-to-find Nato LP; perhaps that's just as well, since most American listeners could likely relate to the pulp fiction

of Spillane's crime novels more readily than to the more abstract French filmmaker.)

To guide the combined efforts of his ensemble, Zorn made use of a series of file cards, each of which contained an idea or impression gleaned from author Mike Hammer's literary ouevre --bloodcurdling screams, sleazy bar saxophone, twanging and searing guitars, and of course, John Lurie's laconic, world weary narration. The music drastically changes from moment to moment, yet somehow, a satisfying unified whole is the result: In effect, the dramatic subect serves to unify the composition in much the same way as classical form or tone rows had served in previous eras. Perhaps most incredibly of

all, while Spillane sounds like a piece that could only have been achievedin the controlled circumstances of a studio recording, Zorn went on to lead ensembles in a handful of breathtaking live performances in subsequent years. Despite its patchwork origin, Spillane breathes, snaps, howls andtumbles into the gutter like a living organism. Nothing overstays its welcome; nothing goes to waste. (In fact, a handful of cast-offs from Spillane were absorbed into Zorn's incidental music for the Mabou Mines production The Bribe, which was recorded at the same time in the same studio with most of the same musicians, but remained unreleased until 1998. The score almost sounds like an extended meditation on the themes and moods of Spillane.)

The two other works on the original Nonesuch disc are nearly as fascinating: Two-Lane Highway is nothing less than a concerto for the great electric bluesman Albert Collins. To accomodate the soloist's laconic drawl and wailing leads, Zorn slowed the pace of this dusty imaginary Texas travelogue. Collins is shadowed by the eerie wail and Hendrix murmurs of Robert Quine's guitar, buttressed by the fat, rich chords of Big John Patton's organ, and prodded along by bassist Melvin Gibbs and dual drummers Previte and Ronald Shannon Jackson. It's a fascinating glimpse at a

compositional format that Zorn was not to revisit. Forbidden Fruit wedded the Kronos Quartet and turntable artist Christian Marclay (using recordings of music for strings only) into a disquieting and frequently cacophonous web of scapes, plucks, ghostly whirrs and Grosse Fuge snippets to back the cooing of vocalist Ohta Hiromi. Ifthe piece doesn't reach the heights of the brilliant works Zorn would go on to write for Kronos in subsequent years, still, the birth of one of Zorn's most significant artistic relationships of the decade remains eminently listenable and a giddy thrill

ride.

While most of the music from that particular period in New York's musical history sounds comfortable and familiar -- and some, indeed, perhaps awkward and dated -- Spillane maintains a sense of weird mystery and self-sufficiency. Who's screaming at 8:50? Presumably that's Zorn drunkenly singing just ten seconds later? And just who is ranting in Russian at the 16-minute mark? Even with the passing of 16 years, the piece refuses to divulge all of its secrets, and yet it is so distinctive and instantly recognizable that enough that the piece can be easily identified by couple of drums beats, a guitar riff and a sax lick sampled on Amon Tobin's track "Cruzer" (from the 1997 album Adventures in Foam, released under the name Cujo). Zorn reissued Spillane on his own Tzadik imprint in 1999, paired at last with Godard. To my mind, that's a mixed blessing: Great to have the earlier piece more easily accessible, but while Spillane the composition is a masterpiece, Spillane the album was no less estimable. Indeed, in 1987, it

was the call of the wild, and it remains utterly sui generis.

Comments and Feedback:

|