| |

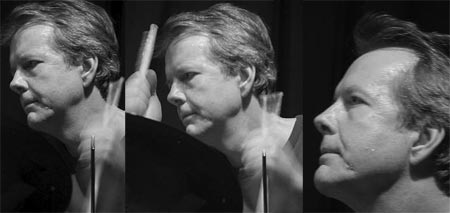

[Photo: Peter Gannushkin] |

The Best Kept Secret in the East

Tom Rainey Sits Behind the Kit for Tim Berne, Mark Helias and Tony Malaby. Surely You've Noticed

By Matt Rand

Drummer Tom Rainey and saxophonist Tony Malaby looked like opposites performing at Brooklyn's Barbes with bassist Mark Helias' Open Loose. Malaby was turning back and forth at his waist, letting the bell of his horn project its sound waves left and right and left again. He shook his left elbow on occasion, showing his excitement at the notes he was fingering. Sometimes, his eyes opened wide, either exasperated or surprised.

But Rainey was another story entirely. His facial muscles seemed deadened, and his limbs only moved to play the drums. His movements looked heavy and deliberate. His overall affect seemed one almost of boredom. ("Don't take it personally," joked Tim Berne, a saxophonist and composer with whom Rainey has worked in various ensembles since the early 1980s, of Rainey's flat facial expression.)

And yet, with improvised music, the appearance of exertion is generally important. If music is being played for the first (and only) time, is not just a reordering of memorized licks, then we expect that we will see musicians stretching to the edge of their abilities. And, stretching to the edge of one's abilities usually inspires telltale visual cues: pained or rapturous expressions, sweat, oddly-timed laughs, uncontrolled body movements.

That's what we've come to expect at improvised shows, in addition, of course, to great music. Rainey doesn't make strange facial expressions when he plays. He doesn't grunt or shake. He just plays great music.

"He's gotta be the most underrated musician I've ever seen," said Berne. "I don't know anybody who's on as many records, plays with as many different, really great people, who doesn't get any attention."

Berne is a bandleader who has his own record label, Screwgun Records, and he knows a thing or two about getting attention. But, he said, Rainey doesn't have the instinct for it. "I think it's 'cause he doesn't have any aspirations as a bandleader. And he doesn't come off the bandstand and start selling his shit; he's just really into the gig and that's it. He doesn't have that much patience for the bullshit that you have to do to get attention."

Born and raised in Santa Barbara, California, Rainey said he started playing the drums before he can remember. In junior high and high school, he studied standard school percussion instruments like timpani, marimba and vibraphone, but he also played drums to rock music.

"My first professional experience was playing with a dance band," Rainey said. "At the time I loved it. Top 40 music at that time was very interesting. There was such a variety of stuff that was musically at the risk of sounding like some old fogey a lot more interesting than the stuff they're dancing to today. They were real bands; now I guess you'd have to go out and do, I don't know, Britney Spears covers or something. But back then you were playing Steely Dan, Chicago, Santana; it was really a variety of bands, some of which I still really like."

In 1975, he headed east for Boston to go to the Berklee College of Music. He was eager to get better at playing the drums, but "dropped out after my first semester. The drum teacher I had I think he was probably just out of Berklee himself he had me play for him, and he said, 'Yeah that sounds good; we'll come in once a week and talk about drumming.' I thought, 'I don't need to pay tuition for this; I mean, I do that with my friends.'"

When Rainey finally ended up in New York, he was just in time for the loft scene to end. His first gig in New York was with Mike Nock, which Rainey said impressed him because "he had an album out." He also played with Ratzo Harris and Tom Harrell, and then Kenny Werner. In the early '90s, he started doing gigs with Fred Hersch.

By the mid '90s, Rainey was playing steadily with the two bandleaders that would come to be his most valuable musical associations, Tim Berne and Mark Helias.

Berne said that, "With Paraphrase in 1995, I think, that was the first time that [Rainey] really had an equal part in what was going on musically. And from that point on, I think his playing really grew amazingly. He became a lot more confident about imposing his ideas on the situation, even when we were playing written music, and he stopped acting like a sideman."

As a sideman, Rainey said he can get bored. No matter how good a soloist is, if he feels like it's the third solo in a row after two other solos, Rainey said, he's lost interest. "I hate being on a gig and thinking this tune should have ended 5 minutes ago."

Both Berne and Helias, instead, offer Rainey opportunities for his ideas to become integral parts of the music when it is performed or recorded. Plus there's a great deal of comfort involved for Rainey. "All those bands, they're all my best friends. It's a lot more than just playing music; we've got our rapport on the bandstand but also socially," he said. "As a creative improvising musician, I couldn't be in a better situation in the world. If I'm going to get bored with these guys, then I should look for another line of work."

In Berne's and Helias' bands, sections of a song are composed and sections are improvised. But even with the composed sections, Berne and Helias generally leave the drum part blank, letting Rainey develop his own part. Helias said that Rainey is "great at processing a piece, sometimes a very complex piece, and just orchestrating his playing. And as we learn it and get more deeply involved in it, then we can start deconstructing it, and really superimposing he really gets oblique after a while."

Berne described the process similarly. "In the beginning, it's the densest because he's playing everything, because he's such a good reader. Then he'll strip it away. Once he internalizes it and finds an approach, he really varies it."

Berne added that he felt that Rainey's playing on 2003's The sublime and. (Thirsty Ear) was as good as he's ever heard Rainey recorded. The disc is a live recording of Berne's Science Friction band, which includes longtime collaborators Craig Taborn on keyboards and Marc Ducret on guitar. On it, among several other tracks, is a song called "The Shell Game," which was the title of Berne's previous release (with Taborn and Rainey), though not the title of any of the tracks on that release.

The piece incorporates elements from a few of the songs on The Shell Game (most closely approximating "Twisted/Straight Jacket"), but there's a lot more going on explicitly in terms of harmony than there was on the disc of the same name, mainly because of the addition of another harmonic instrument in the guitar. But Rainey's reactions to the differences could have been simplistic. He could have just sat back and outlined where the music was going, or went on its original versions, trying not to crowd out the sound with too much playing. And at some points this is what he does. He lets Taborn and Ducret play off of Berne's melodies with only the slightest of rhythmic accents behind them. But then Ducret takes off on a pyrotechnic solo and Rainey grooves hard with Taborn behind it. As the solo evolves, Rainey takes a more active role, varying his beats to keep Ducret's playing sounding like it's unfolding, as opposed to stagnating, as it might have had Rainey just sat in the same groove.

And then Rainey's solo, which follows a return, more or less, to the head, accomplishes in its evolution precisely what Berne said makes Rainey's solos so good: "His solos are always very transitional, from what's happening before to what's happening next. It sounds easy, but with most people, the solo's the shit and maybe the last ten seconds or so are setting up what's happening next."

Taking that one step further, Rainey doesn't just have a mastery of transitions of time; he also is adept at transitioning between any one part of the drum set and another. On Tony Malaby's recent release Apparitions (Songlines, 2003), Rainey is one of two drummers. Rather than antagonizing each other or getting bogged down in headcutting, however, he and Michael Sarin begin to sound like one drumset. A shared solo finds them following each other around their two drum sets, moving with a rare sympathy, even though Rainey said that he was at first skeptical about the idea of doing an album with two drummers.

It is this kind of adaptability that makes Rainey so good. He can internalize a piece of music in any situation and leave his mark on it.

"Everybody I've ever worked with, there's been areas that I've avoided just 'cause it wasn't the best situation for that person or for the combination or whatever," Berne said. "But I can't say with Tom that there's anything I really avoid."

Comments and Feedback:

More Recent Reviews, Articles, and Interviews @ The Squid's Ear...

|

|