After dying my hair the color of tangerine — with grapefruit and black olive blotches — at age sixteen, my mother, unable to grasp why I insisted on rebelling in ways that garnered bruises and black eyes at school, ended a tearful conversation with the desperate query, "Why are you just trying to make yourself look ugly?" I imagine a similar dialog occurred once or twice between vocalist Ute Wassermann and her parents: "Honey, sing the Hayden. Why did we pay for all this schooling? Why do you only make flatulence and joke sounds with your mouth? You make the dogs howl!"

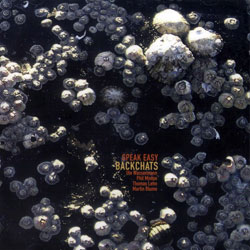

Created from Thomas Lehn's analogue synthesizer, Wassermann and Phil Minton's unaffected voices and Martin Blume's percussion, Backchats is an inventive, nervous, unsettling-yet-resplendent collection of tracks that belie the mild-mannered photo of the quartet, set up in an airy Cologne loft, from the sleeve insert. Going beyond mere lip smacks and pops and into demonic territories with unprecedented, infernal, guttural purges, Minton and Wassermann lead the works with innumerable unhinged extended vocal techniques: they squeak, snarl, groan, manifest as reverent phantasms, whisper with perverted intent, offer aborted mid-frequency radio broadcasts, resemble police sirens summoned due to mating marine mammals on the Interstate, rise from infant mites to wheezing elderly giants — and back again — form sentences with only consonants, shout obscenities using only vowels, flutter like wild horses, spasm uncontrollably from near-throat singing to mongrel scat, et cetera.

Lehn follows with his EMS Synthi, reeling out gravely pops and clicks, staccato pings of spring reverb, brief washes of high-pitched sine waves, thorny horns, sputtering bird calls, bits of Morse code, vinyl cracks and arpeggiations. In the background, Blume works with shadows of this already obscured imbroglio, maintaining his own penumbra of wispy cymbal rolls, murky tom-tom thumps, bassy bells, bongos, two-second outbursts, bowed cymbal, Gamelan, grumbling bass drums and brushed snares; though often drowned out by Wassermann and Minton, his gentle output stabilizes the group like the foundation of a flamboyant modern structure — one made of balloons, multi-colored ribbons and braided cellophane — that would otherwise float away.

The album might, on the surface, resemble live Foley work, a recount of a twelve-hour conversation compacted into fifty-three minutes and/or the soundtrack to the "too odd, even for us" Looney Toons archives, but the quartet's work is far from gimmick. The sheer number of patterns and transmogrified personalities each member dexterously flaunts confirms a complexity very few can grasp let alone perform. Though their mothers might not understand the aesthetic (Minton's singer parents probably wonder why they shelled out all that money for trumpet lessons), possessing the ability to sound as "ugly" and "strange" as possible puts the members of Speak Easy at the top of the ladder.

Comments and Feedback:

More Recent Reviews, Articles, and Interviews @ The Squid's Ear...

|