To celebrate drummer/percussionist Eddie Prévost's 80th birthday, Café Oto hosted four concerts once a week in June, 2022, each a differing configuration from Prévost's history; this final concert reconvened for an extended improvisation between Prévost & guitarist Keith Rowe, with a "Postscript" from pianist John Tilbury recorded at his home in January, 2023.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 5.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Keith Rowe-guitar

Eddie Prevost-drums

John Tilbury-piano

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

Includes a 22-page booklet with liner notes by Eddie Prévost, a letter exchange, a brief biography of John Tilbury, and b&w photos of the performers.

UPC: 5020492011228

Label: Matchless

Catalog ID: MRCD112

Squidco Product Code: 33461

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2023

Country: UK

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold w/ booklet

Recorded at Cafe OTO, in London, UK, on July 30th, 2022, by Billy Steiger.

Track two recorded at the artists home in Kent, UK, on Janurary 18th, 2023, by Sebastian Lexer.

"[...] The final week drew the most attention and marked the inevitable stage to which the preceding concerts had been building: not only was it the final performance in the series, but the last ever gig by AMM, of which Prévost has been a member since 1965. Having missed the workshop gig due to Covid, he had, remarkably, recovered in time for the gig. As he announced from the stage, each gig had encountered some kind of hiccup: two of the eight saxophonists absent from the first gig, one musician absent from the second, Prévost himself from the third. And in the event, the AMM gig — sold-out, on a stiflingly muggy day, in the middle of a transport strike — transpired, not as the usual Prévost-John Tilbury-Keith Rowe trio, but as a Prévost-Rowe duo, the piano symbolically covered and moved to the side. As Prévost explained from the stage, Tilbury's mobility issues and health vulnerabilities ultimately meant that live performance is no longer a sensible option.

Given this, and given the finality of the occasion, this was an event in many ways of ghosts and absences. Sombre and intense, the roughly hour-long performance that followed was characterised by a highly concentrated restraint in which past history spoke through the gaps, the breaks, the silences. Mourning has increasingly been a part of AMM and its satellites as the years pass. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Rowe and Tilbury's two duo records, Duos for Doris (2003) and EE — Tension and Circumstances (2011), dedicated to the respective memories of their mothers, women of working-class origins, raised in poverty, who lived into the new century. And in the Q&A that followed after the break, Prévost mentioned that he still thinks of AMM music as "in dialogue" with the long-dead Cornelius Cardew: it was in looking for musicians to play his then-newly composed Treatise that Cardew came across the group, and that score has long been a source for those members who survived him. Now Tilbury, too, though still living, was absent, and Rowe made sure that Tilbury, too, retained a virtual presence, at times sampling portions of his playing: bell-like, circling piano figures like lights flickering and dying away on the music's horizon.

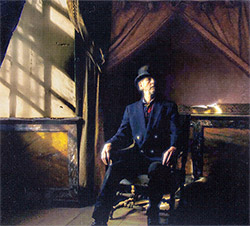

Rowe has had Parkinson's for some years: able to use only one hand while performing, his playing has had to adapt, as he movingly describes Bob Burnett and Alan F. Jones' recent short film What is Man and What is Guitar? (2021), recently made available on YouTube by The Wire. Since his diagnosis eight years ago, he's set aside his tabletop guitar, and on the night seemed to work almost entirely with pre-recorded and sampled material, including what sounded like Rowe's own guitar playing, Tilbury playing Feldman's For Bunita Marcus, sounds from a gagaku performance — alluding to AMM's debut recording session for Elektra, which had been double-booked with a gagaku ensemble — the march from Purcell's Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, and various sine-tone swells. Yet even prior to the diagnosis, Rowe had begun to move away from the chance mechanism of the radio and towards a more curated set of samples, often from classical music. The approach creates, more than ever, a compositional approach to improvisation: structured, sculpted from pre-existing materials, though one might argue that this is no different to the improviser's practice of bringing an instrument, its history, and a set of resources — woodshedded, defined by the possibility and range of personal taste, placement within the history of the music, and of the instrumental means to hand.

Prévost, meanwhile, is less interested in referentiality, more in working with a range of materials in which percussion is treated as textural element: on this occasion, bass drum, snare, bowed tam-tam and cymbals. Prévost has tended towards this approach in recent years — compare earlier AMM performances, particularly when Lou Gare is present, in which broiling rhythmic bursts briefly invoke free jazz, to latter-day AMM, or to a record like Prévost and Jennifer Allum's Penumbræ (2011), on which the duo conduct "investigations" into bowed surfaces, Prévost putting those percussive practices John Mowitt calls "drumming, beating, striking" entirely to the side. Bowed metal and rubbed drumskins form a sound that's continuous yet jagged, pitched yet wavering, percussion treated somewhere between a rhythmic and a timbral entity. There are harsh edges — particularly when Prévost bows the cymbal, even though there is something lulling about the process. It at once emphasizes physicality — minute variations in pressure and strength of arm can alter the nature of the sound — while de-emphasizing the kinds of physical display associated with the drumkit and with percussion. At times, indeed, the percussion effectively plays itself: in this final AMM performance, Prévost left an electric toothbrush vibrating for lengthy periods on the bass drum, added a droning, continuous element in the spirit of AMM's "laminal," evolving textures.

Rowe's and Prévost's respective approaches certainly meshed, at times more than others, but that's not really the point. If early AMM's achievement was to create a group texture in which the lines between instruments and between individuals blurred, AMM as it has come down in history — that's to say, in the Prévost-Rowe-Tilbury line-up — has been more about the negotiation, within certain collective parameters, of three distinct individual approaches. At the same time, the point of AMM is as a kind of holding space: as suggested when, in the post-performance Q&A, Rowe and Prévost good-humouredly refused audience requests to divulge what the AMM acronym stands for. "It stands for this", one of them said, gesturing around the room to indicate, not only the musicians and the still-palpable presence of the music they'd made, but the space that music had been made in, including the audience in the room. There's perhaps a paradox here: an identifiable style — "AMM music" — which has been established for decades now is also about the music as an opening up which is not limited to the musicians on stage. This might be the ghostly dialogue with Cardew, or the virtual dialogue with the sampled Tilbury, but it's not simply a case of the literal inclusion of other voices through Rowe's samples or radio. "AMM has influenced my musical life ... has influenced my life", Prévost remarked before they began to play. AMM is about an approach to material, to liveness, to conceiving a group, that is highly specific to its members, but that also reaches somewhere else. Once more, we come back to "ethic of improvisation" that Cardew emphasized. Cardew quotes Wittgenstein: "To imagine a language means to imagine a form of life". Or, in his own words: "My attitude is that the musical and the real worlds are one. Musicality is a dimension of perfectly ordinary reality. The musician's pursuit is to recognize the musical composition of the world (rather as Shelley does in Prometheus Unbound) ... The subtlest interplay on the physical level can throw into high relief some of the mystery of being alive." In his essay, written ten years before his own death, Cardew further suggests that musical improvisation is a way of reckoning with the fact of death — that "the performance of any vital action brings us closer to death; if it didn't it would lack vitality". But this reckoning — what Cardew calls "acceptance of death" — is not the same as fatalism.

AMM's final concert was both apotheosis and relinquishment. Rowe performed with a cardboard tube on the tabletop: in the Q&A it turned out this this contained the original AMM "icon," a painting that had been proposed for the front cover of their first album on Elektra Records, only to be turned down and replaced by Rowe's now-familiar image of a yellow truck, making its own journey to a bright nowhere. As Rowe explained, the image-apparently a bright, Pop-Art style still life — was a kind of variant on the Annunciation scene, in this case announcing the inception of AMM. Things come full circle. At times, Rowe, bent over the tabletop so that his upper body was almost horizontal, his arm stretched out over his equipment, resembled one of the art-historical depictions he so admires: a Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Dürer's St Jerome, a Rembrandt self-portrait, a meditation on ageing and creativity and continuance.

For the first ten or fifteen minutes, the music was weightily sparse, scratching around the edge of silence: Prévost bowing tam-tam, Rowe providing scratchy flickers and dim washes of Purcell that disappeared almost as soon as they'd appeared. The music was most engaging when it reached higher density: a point at which Rowe had in play four or five layers at once, the laminal thickness of texture at which AMM specialise, an emotive force, a denseness, a thickness, an open and opened area. But success is not the point. As Prévost once remarked in a profile of the group by the writer and composer Kyle Gann: "Ultimately, AMM will fail. There may be rare moments when we, or others, sense a kind of success, but there can never be 'ultimate' success ... The paradox is that continual failure on one plane is success on another". If failure was a preoccupation of AMM's from the beginning, as Prévost relates in the liner notes to AMMMusic, this concern has perhaps assumed greater urgency of late. In recent years, Tilbury has made a series of performances in which he recites Samuel Beckett's text of gradual bodily collapse over sparse keyboard sounds. I saw him give a devastating rendition in the vast surroundings of King's College Chapel a few years ago, an intensely moving meditations on bodily frailty and decay I've witnessed. Likewise, Rowe's reckoning with the deaths of family members, and his coming to terms with his own Parkinson's diagnosis, has reflected itself in how he conceives of the music he makes and the way it's presented. On the live performances released as EE-Tension and Circumstance, on which Rowe and Tilbury paid homage to Rowe's late mother, who'd raised him as a single mother in conditions of post-war poverty. Of the album design, in which Rowe mimics his late mother's handwriting, Rowe remarked: "I wanted it to recall a trace of old age and an increasing lack of facility: I wanted it to look shoddy, with errors, away from those slick images of conceit."

And despite the particular sense of focused intensity when the music thickened and opened out, in this final performance AMM was perhaps most itself when the music was most rebarbatively quiet or activity-free: Rowe bent over his equipment making almost no sound; passages where the music seemed to have frozen, to meander, to have become lost inside a reverie of itself; and, above all, the extraordinary silence that concluded the performance, and AMM itself. Rowe having fallen quiet and sat back a minute or so before, Prévost, too, came to a pause, and they both sat poised, for around a minute or so, the music, the musicians and the audience alike all deciding whether or not it should continue.

The last music AMM made together was that silence: a silence full, replenished, and drained out; an ending that was also an opening. This silence was heavily inflected by the framing, the history, the circumstances and the occasion of the concert and could not accrue the intensity and meaning it did outside those: and why should it? Instead, it felt as if AMM was opening up to us — everyone in the room, and all the listeners and players not in the room, living and dead. [...]"-David Grundy, Point of Departure

"Eddie Prévost turned eighty in June 2022 and to celebrate, Café Oto invited Prévost to convene four separate concerts, held every Saturday of July. Prévost named the residency for a line from Seamus Heaney's "Clearances" — "its heft and hush become a bright nowhere" — which he took as a model for the kinds of utopia modelled in musical improvisation; the series was further dedicated to the late impresario Victor Schonfield, who died early in May. As curator of the Music Now charity in the '60s, Schonfield played a key role in bringing American jazz and free jazz musicians from Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra to Miles Davis to the UK. He also served as part-time manager for AMM, the group with which Prévost over the years has been most indelibly associated — to the extent that Schonfield was jokingly referred to as a member of the group. In the '70s and '80s, Schonfield was active in left politics as chief trade union organiser and treasurer of the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy: in his biography of Michael Foot, Mervyn Jones writes of Schonfield, Vladimir Derer and Jon Lansmann, later founder of Momentum, "they were unreservedly dedicated, they had no political ambitions of their own and they were in a position to work day and night for the cause without pay." And though, during this time, Schonfield's activities as a promoter had taken a back seat, in later years, he was a regular at Oto and a mentor to younger musicians.

The dedication to Schonfield highlighted the importance of those who, though not themselves musicians, are indispensable in facilitating and enabling the music and the culture it creates. It also harked back to that moment in the mid-'60s of a counter-cultural London, where musicians of working-class backgrounds like Prévost and Keith Rowe were able to some sort of lead in reinventing what music might be, even as that music has tended to fly under the radar of national and international cultural institutions. All those decades on, the series, with Prévost himself in the role of curator and organiser that Schonfield occupied, manifested a continuing dedication to improvised music as collective, social endeavour. Its generational sweep reflected the various stages and facets of Prévost's career and his firmly collaborative ethos, both centring and moving beyond his own individual role. As a music that is about collaboration, removing the format of the solo for an entirely collective music, free improvisation does not naturally lend itself to narratives of heroic, solitary genius, though sometimes those narratives inflect the way its history has been passed down to us. For Prévost, however, the approach to — or enabled by — improvisation, first discovered in AMM, and later expanded in his various theoretical books on improvisation, insists on the collective dimension first and foremost. As he wrote in the liner notes for the CD reissue of AMMMusic, "A preoccupation with ... with one's own ego at the expense of the ensemble is destructive."

Over the course of Bright Nowhere, watching each event unfold in its difference was watching process at work: not just a historical assembly, a chronological survey, or a potpourri, but a manifestation of the simultaneous openness and focus that can still be found in freely improvised music nearly sixty years since Prévost first began playing it. The figure of travel that Prévost added to Heaney's phrase — "marking a journey to a bright nowhere" — might suggest progression towards a goal, but-as in the fascination with notions of wandering, errancy, and travelling in Luigi Nono's late work — it instead complicates these ideas, blurring borders and boundaries, while refusing to give up on the hopes for better — political, social, human — brought to bear on aesthetic experimentation."-David Grundy, Point of Departure

Includes a 22-page booklet with liner notes by Eddie Prévost, a letter exchange, a brief biography of John Tilbury, and b&w photos of the performers.

The Squid's Ear!

Get additional information at Point of Departure

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Keith Rowe "tabletop guitarist and painter. Rowe is a founding member of both the influential AMM in the mid-1960s (though in 2004 he quit that group for the second time) and M.I.M.E.O. Having trained as a visual artist, Rowe's paintings have been featured on most of his own albums. After years of obscurity, Rowe has achieved a level of relative notoriety, and since the late 1990s has kept up a busy recording and touring schedule. He is seen as a godfather of EAI (electroacoustic improvisation), with many of his recent recordings having been released by Erstwhile Records. Rowe began his career playing jazz in the early 1960s-notably with Mike Westbrook and Lou Gare. His early influences were guitarists like Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian and Barney Kessel. Eventually, however, Rowe grew tired of what he considered the form's limitations. Rowe began experimenting, slowly and gradually. An important step was a New Year's resolution to stop tuning his guitar-much to Westbrook's displeasure. Rowe gradually expanded into free jazz and free improvisation, eventually abandoning conventional guitar technique. This change in his approach to guitar, Rowe reports, was partly inspired by a teacher in one of his painting courses who told him, "Rowe, you cannot paint a Caravaggio. Only Caravaggio can paint Caravaggio." Rowe reports that after considering this idea from a musical perspective, "trying to play guitar like Jim Hall seemed quite wrong." For several years Rowe contemplated how to reinvent his approach to the guitar, again finding inspiration in visual art, namely, American painter Jackson Pollock, who abandoned traditional painting methods to forge his own style. "How could I abandon the technique? Lay the guitar flat!" Rowe developed various prepared guitar techniques: placing the guitar flat on a table and manipulating the strings, body and pick-ups in unorthodox ways to produce sounds described as dark, brooding, compelling, expansive and alien. He has been known to employ objects such as a library card, rubber eraser, springs, hand-held electric fans, alligator clips, and common office supplies in playing the guitar. A January 1997 feature in Guitar Player magazine described a Rowe performance as "resemble a surgeon operating on a patient." Rowe sometimes incorporates live radio broadcasts into his performances, including shortwave radio and number stations (the guitar's pick-ups will also pick up radio signals, and broadcast them through the amplifier). AMM percussionist Eddie Prévost reports that Rowe has "an uncanny touch on the wireless switch", able to find radio broadcasts which seem to blend ideally with, or offer startling commentary on, the music. (Prévost, 18). On AMMMusic, towards the end of the cacophonous "Ailantus Glandolusa", a speaker announces via radio that "We cannot preserve the normal music." Prevost writes that during an AMM performance in Istanbul, Rowe located and integrated a radio broadcast of "the pious intonation of a male Turkish voice. AMM of course, had absolutely no idea what the material was. Later, it was complimented upon the judicious way that verses from The Koran had been introduced into the performance, and the respectful way they had been treated!" In reviewing World Turned Upside Down, critic Dan Hill writes, "Rowe has tuned his shortwave radio to some dramatically exotic gameshow and human voices spatter the mix, though at such low volume, they're unintelligible and abstracted. Rowe never overplays this device, a clear temptation with such a seductive technology - the awesome possibility of sonically reaching out across a world of voices requires experienced hands to avoid simple but ultimately short-term pleasure. This he does masterfully, mixing in random operatics and chance encounters with talkshow hosts to anchor the sound in humanity, amidst the abstraction." " Some accounts report that Rowe's guitar technique was an influence on Pink Floyd founder Syd Barrett: "Taking his cues from experimental guitarist Keith Rowe of AMM, Barrett strived to push his music farther and farther out into the zone of complete abstraction." Rowe has worked together with numerous composers and musicians, including Cornelius Cardew, Christian Wolff, Howard Skempton, Jeffrey Morgan, John Tilbury, Evan Parker, Taku Sugimoto, Otomo Yoshihide, Sachiko M, Oren Ambarchi, Christian Fennesz, Burkhard Beins, Kurt Liedwart, Toshimaru Nakamura, David Sylvian and Peter Rehberg. ^ Hide Bio for Keith Rowe • Show Bio for Eddie Prevost "Eddie Prévost (Edwin John) (born Hitchin, Hertfordshire, England, 22 June 1942) is an English percussionist noted for founding and participating in the AMM free improvisation group. Of Huguenot heritage, Prévost's silk weaving ancestors moved to Spitalfields in the late 17th century. Brought up by single parent mother (Lilian Elizabeth) in war-damaged London Borough of Bermondsey. He won a state scholarship to Addey and Stanhope Grammar School, Deptford, London, where to-be drummers Trevor Tomkins and Jon Hiseman also studied. Music tuition, however, was limited to singing and general classical music appreciation. Enrolled in the Boy Scouts Association (19th Bermondsey Troop) to join marching band. As a teenager began to get involved with the emerging youth culture music; skiffle, before being introduced to a big jazz record collection of a school friend with rich parents. With a bonus from the florist, for whom Prévost worked part-time after school, purchased his first snare drum from the famed Len Hunt drum shop in Archer Street (part of London's theatre land). After leaving school at sixteen Prévost was employed in various clerical positions whilst continuing his musical interests. Although, by now immersed in the music of bebop, his playing technique was insufficient for purpose. New Orleans style jazz ('trad') offered scope for his growing musical prowess. He played in various bands mostly in the East End of London. It was during a tenure with one of these bands he met trumpeter David Ware, who also shared a passion for the hard-bop jazz music. In their early twenties they later formed a modern jazz quintet which ultimately included Lou Gare, who had recently moved to London from Rugby and was a student at Ealing College of Art and a member of the Mike Westbrook Jazz Orchestra. AMM was co-founded in 1965 by Lou Gare, Eddie Prévost and Keith Rowe. They were shortly joined by Lawrence Sheaff. All had a jazz background. They were, however, soon augmented by composer Cornelius Cardew. Thereafter, Cardew, Gare, Prévost and Rowe remained as basis of the ensemble until the group fractured in 1972. Other more formally trained musicians were to enter the ranks of AMM after Cardew's departure. Those to make significant contributions were cellist Rohan de Saram and, in particular, pianist John Tilbury. The latter was a friend and early associate of Cardew and later became his biographer. In contrast to many other improvising ensembles, the core aesthetic of the ensemble is one of enquiry. There was no attempt to create a spontaneous music reflecting, or emulating, other forms. The AMM sound-world emerged from what Cardew referred to as "searching for sounds". For Prévost, the following would become the core formulation which he would explore during his subsequent musical career and explain and develop in various writings (see bibliography) and workshop activities. We are "searching" for sounds and for the responses that attach to them, rather than thinking them up, preparing them and producing them. In the 1980s, in response to various workshops and lectures, Prévost first formulated the twin analytical propositions of heurism and dialogue as defining concepts for an emergent musical philosophy, whilst acknowledging Cardew's construction (above). This line was explored and constantly redefined much through the London workshop experience, as his articles and his books show. (see below: The London Workshop). His 2011 book - The First Concert: an Adaptive Appraisal of a Meta Music - is described as a view "mediated through the developing critical discourse of adaptionism; a perspective grounded in Darwinian conceptions of human nature. Music herein is examined for its cognitive and generative qualities to see how our evolved biological and emergent cultural legacy reflects our needs and dreams. This survey visits ethnomusicology, folk music, jazz, contemporary music and "world music" as well as focusing upon various forms of improvisation - observing their effect upon human relations and aspirations. However, there are also analytical and ultimately positive suggestions towards future metamusical practices. These mirror and potentially meet the aspirations of a growing community who wish to engage with the world - with all its history and chance conditionals - by applying a free-will in making music that is creative and collegiate." (back cover of First Concert)History with AMM When, in the early 1970s, Cardew and Rowe began to devote their time and energy to espousing the political doctrine of an English Maoist party a fracture occurred in the ensemble leaving the rump of Lou Gare and Eddie Prévost, who continued in a duo form making various concerts and festival appearances and leaving a legacy of two recordings. At the end of the decade a rapprochement was attempted and for a short while the quartet began playing together again. It did not last. Lou Gare departed and moved from London to Devon. While Cardew's commitment to politics made his complete withdrawal inevitable. It was during this period Prévost took an Honours Degree at Hatfield Polytechnic, exploring and developing his interests in history(especially East Asian) and philosophy. Musically, this left Rowe and Prévost playing together. Their recording for German ECM label "It had been an ordinary enough day in Pueblo, Colorado" is the single example of their duet period. By the late 1970s a reawakened association with John Tilbury was cemented into his permanent place in AMM. He is featured on all subsequent AMM performances and recordings (as is Prévost). In 2002 a more lasting schism occurred leading to Rowe departing from AMM and leaving Tilbury to continue with Prévost.Percussion The investigative dynamic of AMM leads a musician to seek out new material. It is the fabric and constitution of stuff that is considered as more important than any historical or cultural heritage. It is Prévost's constant exploration's that has produced the range of sounds associated with his work, particularly within AMM and its extension to the many workshop ensembles. This philosophy leads to what Seymour Wright has so aptly described as the "awkward wealth" of investigation.(citation) It is a position of constant examination and artistic redress.Drumming Drumming with AMM was principally replaced by discreet percussion work which by and large relied on sound and texture rather than rhythm. At the time of the Gare/Prévost period this position was reviewed. However, it was plain the AMM aesthetic, characteristic of the early formative period, was to have its effect. The "searching" method prevailed. And, whereas a saxophone and drums duet led to a more jazz-like expectation (amplified by Gare's reversion to a more rolling and modal post-Rollins kind of approach). Prévost's playing was noted to have acquired some unusual qualities. This lead one reviewer (Melody Maker) to remark in 1972: "His free drumming flows superbly making use of his formidable technique. It's as though there has never been an Elvin Jones or Max Roach." Drumming however, was to take a back seat in Prévost's musical output as AMM developed and began to acquire and enhance its innovative reputation. And, apart from rare musical outings he did not commit himself, more fully, to the jazz drum kit again until 2007/08. Although, continuing to play percussion, a jazz-inflected project with Seymour Wright and Ross Lambert in an ensemble called SUM was the precursor of a period more devoted to drumming. Apart from various ad hoc ensembles, this led to various recordings including a series a CDs entitled Meetings with Remarkable Saxophonists. At date this consists of four volumes featuring Evan Parker, John Butcher, Jason Yarde and Bertrand Denzler respectively.The London workshop Over the years Prévost has conducted many improvised music workshops. However, as a result of a seminar he conducted at The Guelph Jazz Festival, Canada in 1999, Prévost began to formulate a framework for a workshop based upon a more thorough working of AMM principles and practice. He wrote: "I had, of course, already had long previous experience of improvisation and experimental music mostly through my participation in AMM and working closely with the composers Cornelius Cardew and Christian Wolff. From this experience I had begun a working hypothesis in my book 'No Sound is Innocent'. However, there is always more to discover. On my long flight across the Atlantic, I intuited more could be found out. Not through introspective, if rational, thought alone but, through discovery or experimentation: praxis. It can, of course, be very discomforting to watch a proposition die in practise. No theory is worth its salt unless it is fully tested. The best ideas - this experience suggests - emerge through activity. Hence, the working premise of the improvisation workshop had to be based upon an emergent set of criteria constantly tested within the cauldron of experience. In November 1999 I made it known that a free improvisation workshop would start weekly in a room at London's Community Music Centre, near London Bridge. Originally, under the auspices of the London Musicians' Collective, [...] these premises were found and minimal lines of communication to possible interested parties were opened. The first Friday evening (not thought to be an auspicious evening of the week because people 'went out' to have a good time) duly arrived. The room was available precisely because no one ever hired it on a Friday! I waited. Edwin Prévost, The First Concert: an Adaptive Appraisal of a Meta Music, (2011) p.115/6 Since then the workshop has continued weekly. It has a strong collegiate atmosphere. Those who participate are themselves formulating and refining a programme of enquiry and empathy. The working premise is one of 'searching for sounds' (Cardew). The emphasis is upon discovery and not on presentation. It is a place to risk failure and develop an open and continuing processive relationship with the materials at hand and other people. As hoped and anticipated, Prévost's continual presence is no longer required. In his occasional absences senior colleagues (in particular Seymour Wright and Ross Lambert) more than adequately move the project along. To date there have been over five hundred people who have attended the weekly workshop in London, representing over twenty different nationalities. This activity is further augmented by occasional forums for discussion and London's Cafe OTO programmes ensembles drawn from the London workshop every month. There have also been occasional extended periods of collective workshop musical experimentation. And, in 2010 there was a residential workshop held in Mwnci Studios on the Dolwillym Estate, west Wales. (see various other texts: including Philip Clark's Wire piece)] There are now workshops based upon this general premise functioning in Hungary, Greece, Slovenia, Japan, Brazil and Mexico. Mostly started by alumni of the original workshop in London.Intermediate and experimental compositions Cardew's 'Treatise' etc. Cardew's introduction to AMM in 1966 owes something to his search for musicians to perform his (then unfinished)193 pages long graphic score, 'Treatise'. The AMM musicians (at the time Lou Gare, Eddie Prévost, Keith Rowe and Lawrence Sheaff) seemed perfect candidates to embrace this bold work of imagination. And, with others (including later AMM member John Tilbury) all participated in the premier performance at the Commonwealth Institute on 8 April 1966 (check year!). But the initial impact of Cardew's induction into AMM was to bring a halt to his compositional aspirations. However, over the years since, AMM has had a long relationship with particular indeterminate and experimental works particularly those of Cardew - especially after his death in 1983. Most prominently 'Treatise'. Other favourites were 'Solo with Accompaniment', 'Autumn '60', Schooltime Compositions' and the text piece Cardew wrote particularly for AMM, 'The Tiger's Mind.' These pieces (which for a long time had been neglected within 'new' musical schedules), and occasionally others by Christian Wolff and John Cage, were sometimes played in conjunction with an AMM improvisation. Some concert promoters were, it seems, more interested in these pieces being played than the principal musical output of AMM. Hence, Prévost's ambivalence about the inclusion of such material in concert programmes. The creative search for primary performance material was diverted, in such works, in keeping with the demands of the notation or compositional scheme. This inevitably prevented the musician from (to use Cardew's own words) "being at the heart of the experiment". (Cardew, 'Towards an Ethic of Improvisation; CC R p. 127).Matchless Recordings and Publishing In 1979 Prévost began the recording imprint of Matchless Recordings and Publishing. Although there had been some interest by commercial labels to take on the new improvising music of the late 1960s onwards, it proved not to be satisfactory or long-lasting. Together with a number of similar initiatives, e.g. Incus Records in Britain and ICP (?) in the Netherlands, Prévost sought to take control of their own work. In the early years this was slow and painstaking work. Some years little was produced and few small sales accrued. Gradually however, Matchless recordings began to be the documenting and disseminating base for a developing body of work. Most of the AMM output is featured on Matchless and this has diversified (more so in recent years) to include other associated artists and ensembles.[see matchlessrecordings.com] In 1995, following the same principal for internal control over the output, production and dissemination of material, the publishing imprint Copula was inaugurated. The first publication was Prevost's No Sound is Innocent. Later followed by Minute Particulars in 2004. 2006 saw the publication of Cornelius Cardew: A Reader (edited by Prévost) which was a collection of Cardew's published writings accompanied by commentaries by a number of musicians associated and inspired by Cardew. This volume was an essential companion to John Tilbury's comprehensive biography Cornelius Cardew: a life unfinished which was also published by Copula in 2008. The most recent book to appear on this imprint is Prévost's The First Concert: An Adaptive Appraisal of a Meta Music (2011). Eddie Prévost is the cousin of the ex-docker shop-steward and left-wing political activist also named Eddie Prevost." ^ Hide Bio for Eddie Prevost • Show Bio for John Tilbury "John Tilbury (born 1 February 1936) is a British pianist. He is considered one of the foremost interpreters of Morton Feldman's music, and since 1980 has been a member of the free improvisation group AMM. Tilbury studied piano at the Royal College of Music with Arthur Alexander and James Gibb and also with Zbigniew Drzewiecki in Warsaw. 1968 he was the winner of the Gaudeamus competition in the Netherlands. During the 1960s, Tilbury was closely associated with the composer Cornelius Cardew, whose music he has interpreted and recorded and a member of the Scratch Orchestra. His biography of Cardew, "Cornelius Cardew - A life unfinished" was published in 2008. Tilbury has also recorded the works of Howard Skempton and John White, among many others, and has also performed adaptations of the radio plays of Samuel Beckett. With guitarist AMM bandmate Keith Rowe's electroacoustic ensemble M.I.M.E.O., Tilbury recorded The Hands of Caravaggio, inspired by the painter's The Taking of Christ {1602). In this live performance, twelve of the members of M.I.M.E.O. were positioned around the piano in a deliberate echo of Christ's Last Supper. The thirteenth M.I.M.E.O. member (Cor Fuhler) is credited with "inside piano" as he interacted and interfered with Tilbury's playing by manipulating and damping the instrument's strings, essentially doing piano preparation in real time. Critic Brian Olewnick describes the album as "A staggering achievement, one is tempted to call The Hands of Caravaggio the first great piano concerto of the 21st century." Another notable recent recording of Tilbury's was Duos for Doris (like The Hands of Caravaggio also on Erstwhile Records), a collaboration with Keith Rowe. It is widely considered a landmark recording in the genre of electroacoustic improvisation (or "EAI"). In 2013 he collaborated with artist Armando Lulaj in FIEND performance at the National Theatre of Tirana (Albania)." ^ Hide Bio for John Tilbury

11/20/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

11/20/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

11/20/2024

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Last Calls 53:04

2. Postscript 13:22

Matchless

Improvised Music

Free Improvisation

European Improvisation, Composition and Experimental Forms

Jazz

Trio Recordings

Keith Rowe

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Top Sellers for 2023 by Customer Sales

Search for other titles on the label:

Matchless.

![Guy, Barry / Ken Vandermark: Occasional Poems [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34849.jpg)

![Novoa / Carter / Mela Trio: Vol.1 [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35236.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Evans, Peter (Evans / Eldh / Black): Extra [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35279.jpg)

![McPhee, Joe: Straight Up, Without Wings [BOOK]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35454.jpg)

![Jeck, Philip: rpm [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35455.jpg)

![Barker / Parker / Irabagon: Bakunawa [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35533.jpg)

![Blaser, Samuel / Marc Ducret / Peter Bruun: Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground [VINYL 10-inch]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35492.jpg)

![Warren, Kenny (Warren / Hoffman / Ellman): Sweet World [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35451.jpg)

![Blake, Ran / Dave Knife Fabris: Live Amsterdam 2006, First Visit [CD + POSTCARDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35275.jpg)

![DNS: Taking Big Bites Of The Khandas Three Cafes Deep [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35334.jpg)

![Cleaver, Gerald: The Process [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34966.jpg)

![Alva Noto: HYbr:ID II [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35201.jpg)

![Baron, Derek / Luke Martin: Distinct and Concealed [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35079.jpg)

![Lyle, Erica Dawn : Colonial Motels [CASSETTE + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35080.jpg)

![Sanna, Claudio: Compositori Sardi Contemporanei II [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35317.jpg)

![Zurria, Manuel: Fame di Vento [3 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35167.jpg)

![Granberg, Magnus / Nattens Inbrott / Skogen: Holde Traume, Kehret Wieder! [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35038.jpg)

![Frey, Jurg: Outermost Melodie [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35039.jpg)

![Pavone, Jessica: Reverse Bloom [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34895.jpg)

![Modney (Modney / Wooley / Gentile / Roberts / Pluta / Symthe / ...): Ascending Primes [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34852.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Haino, Keiji: Black Blues [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35109.jpg)

![Surplus 1980: Illusion of Consistency [CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35069.jpg)

![Staiano, Moe: Away Towards the Light [VINYL + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35037.jpg)

![Caveira (Gomes / Sousa / Abras / Ferrandini): Ficar Vivo [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34643.jpg)

![Gregg, J. J. / David Van Auken: Lunar Prairie [CD w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34611.jpg)

![Coultrain: Mundus [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/32439.jpg)

![Mattin: Songbook #6 [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/27317.jpg)

![Punkappella: Wake Up [7-inch VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17519.jpg)

![Residents, The: WARNING: UNiNC.: Live And Experimental Recordings 1971-1972 [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/31521.jpg)

![Coultrain: Phantasmagoria [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/30142.jpg)

![Lennon, Sean Ono: Asterisms [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34517.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)