There's a sense in which you only need one record by The Necks. And it's by that same token that you also need all of them. The Australian piano trio's formula is so good, or rather they are so good at their formula, that each recording, each concert, seems to be a restatement of the theme. That being: start slowly, move slowly, repeat often. They combine the warmth of jazz with the structuralism of minimalism to make a music that is full of beautiful tension, and something not quite like anything else.

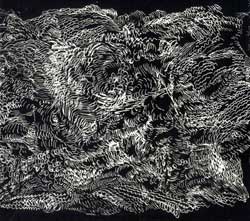

Silverwater, the band's first studio album since 2006, isn't the only exception that proves the rule. They varied form on their second record, 1990's Next, as well as on the 1998 soundtrack recording The Boys, creating shorter tracks rather than their usual hour-long musical monolith. The 67 minutes of Silverwater seem to combine those two facets. It's more varied than usual, with the piano / double bass / percussion triangle augmented at times by organ and electric guitar. Along with the added instruments, the band moves more quickly, or at least more dramatically, through different passages, but ever with the organic feeling of spontaneous discovery. In the world of regular music, this might be called a "suite"; within the unusual aesthetic of The Necks, we can stumble over the differentiation of new motivations within the larger realization, or we can just accept the pasture for what it is: a wide-open, pastoral field, teeming with activity.

The added instruments suggest something else about their working method as well. The only credits on the disc lie in the "Abrahams / Buck / Swanton" writing credit, so the organ and guitar are left unacknowledged. Presumably it's Chris Abrahams at the organ, and drummer Tony Buck plays guitar in other projects so he may be responsible here, but whoever is responsible, no one drops out the first time the guitar comes in so there is some multi-tracking going on, making the middle third of the piece busier than anything heard before on a Necks disc. The band has never been averse to studio manipulation; 1996's Silent Night, for example, contained sound effects (footsteps and such) lifted from films. But here they transmogrify into a virtual ensemble. Buck's timekeeping can be so machinelike it's scary, but here the listener might wonder if that's actually a rattle being looped. It's not a cheat, it just heightens the mystery. Seeing them live already leaves you with jaw dropped, wondering how they did that. Now you have to ask if they even did.

Comments and Feedback:

More Recent Reviews, Articles, and Interviews @ The Squid's Ear...

|