A transformative experience for John Coltrane, whose 1957 studio sessions with pianist Thelonious Monk, recorded after Monk's residency at the Five Spot, came at a transitional point for the iconic tenor saxophonist, expanding his knowledge of harmonic structure and refining his approach to soloing; with Coleman Hawkins, Art Blakey, Gigi Gryce, Ray Copeland, Wilbur Ware and Shadow Wilson.

In Stock

Quantity in Basket: None

Log In to use our Wish List

Shipping Weight: 3.00 units

EU & UK Customers:

Discogs.com can handle your VAT payments

So please order through Discogs

Sample The Album:

Thelonious Monk-piano

John Coltrane-tenor saxophone

Coleman Hawkins-tenor saxophone

Gigi Gryce-alto saxophone

Ray Copeland-trumpet

Wilbur Ware-double bass

Art Blakey-drums

Rossiere Shadow Wilson-drums

Click an artist name above to see in-stock items for that artist.

UPC: 752156116622

Label: ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd

Catalog ID: ezz-thetics 1166

Squidco Product Code: 34197

Format: CD

Condition: New

Released: 2023

Country: Switzerland

Packaging: Cardboard Gatefold

Recorded in NYC, on April 5th, April 16th, June, 26th, 1957, in NYC.

Thelonious Monk With John Coltrane originally released in 1961 as a vinyl LP on the Jazzland label with catalog code JLP-46.

"When - and how - did John Coltrane become John Coltrane, the saxophonist iconic, inspirational, and influential to subsequent generations of jazz artistry? Was it the breakthrough of deep chordal analysis circa "Giant Steps," or the spiritual transcendence of A Love Supreme, or the cathartic transformation of Ascension, "Selflessness," and Meditations? Any or all may apply, as one apparent truth within the complexity of Coltrane's quest was that during his tragically too-short life (he was two months shy of his 41st birthday when he died) he never found an ultimate meaning, a point of perfect expression, a solution to the puzzle of organized sound as manifestation of the breadth of human experience, which he so long sought.

Thus in hindsight we can recognize that Coltrane's musical life was an ongoing, ceaseless, incomplete work in progress; an accomplishment of discovery as growth and growth as change. But it had to start somewhere. My view is that it started, significantly, here, in 1957, as Coltrane began an intensive period of study and rewarding performance with Thelonious Monk.

Prior to this, Coltrane had served a youthful apprenticeship in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges; his first big break was being hired by Miles Davis, on the recommendation of drummer Philly Joe Jones, in 1955. But in that initial term of service with Miles, Coltrane was struggling with a drug habit while simultaneously feeling the necessity to search for his musical identity. For the next two years Miles' quintet recorded frequently, and thanks at first to his connection with bandmates pianist Red Garland and bassist Paul Chambers, Coltrane was called often for sideman duties, primarily at Prestige Records - in 1957 he was in the studio every month from March through December, a total of twenty-two sessions, including the first solely under his own name, in May.

However, a month before this, in April, Miles fired Coltrane and Philly Joe Jones due to unreliability based on their drug dependency. Coincidently, according to Coltrane biographer J.C. Thomas, Monk was at the Café Bohemia the night of the firing, and immediately asked Coltrane to join his group. But learning Monk's music, with its rhythmic alterations and harmonic abstractions, and developing his own method of improvising a solo within its unique qualities, required a considerable amount of analysis and rehearsal. Coltrane acknowledged his permanent debt to Monk in an often-quoted 1960 down beat interview: "Working with Monk brought me close to a musical architect of the highest order. I felt I learned from him in every way - through the senses, theoretically, technically. I would talk to Monk about musical problems and he would sit at the piano and show me the answers just by playing them. ... Also, I could see a lot of things that I didn't know about at all."

Working so closely with Monk during the summer of 1957 provided Coltrane with the kind of specific focus on harmonic structural possibilities that refined and broadened his approach to constructing solos - as can be judged by the increased complexity and confidence of his own Blue Note date, Blue Train, in September. More importantly, we have the evidence at hand.

Those early rehearsals prompted Monk to add Coltrane (and bassist Wilbur Ware) to an otherwise solo piano session in April for a cautiously voiced, slightly ornamented "Monk's Mood." The pianist's commitment to Coltrane was confirmed when he set his tenor alongside that of the great Coleman Hawkins - perhaps intended as another lesson? - for the now-classic Monk's Music album in June. Monk knew what he wanted in organizing this recording - in their original versions "Epistrophy," "Well You Needn't," and "Off Minor" were all hornless, but here fully arranged for four horns, as was the new, evocatively conceived "Crepuscule for Nellie." "Ruby, My Dear" was given as a feature to Monk's old boss Hawkins. It would be wrong to suggest that Coltrane was Hawkins' equal at this stage, but, working from different basic premises, their contrasting approaches display Hawkins' dramatic persona and Coltrane's exploratory ardor.

By July, Monk's quartet with Coltrane, Ware, and drummer Shadow Wilson was in residence at the Five Spot, and, pleased with their progress, Monk booked studio time for them despite the contractual conflicts which prevented a more thorough documentation. These three tunes - also originally recorded as trios - find Coltrane in his next phase of development. The ironic choice of "Ruby, My Dear" (so soon after Hawkins) is fluid and sensitive, "Nutty" is brandished with flourishes, and Coltrane negotiates the ticklish circuitry of "Trinkle Tinkle" with aplomb. Most interesting is that Monk "strolls" (leaving Coltrane without harmonic support) for choruses here and there, recreating their club ambiance where, as the saxophonist related, he was sometimes confronted with fifteen or twenty minutes to solo, freely, with bass and drums - a crash course in inventive self-dependency. Monk, through it all, is Monk, incomparable.

The Five Spot gig ended with the calendar year, and without an assurance of continued income with Monk, Coltrane accepted Miles Davis' offer to rejoin his group in 1958, which would introduce him to modal harmonic resources, the next transition in his quest."-Art Lange, Chicago, October 2023

Artist Biographies

• Show Bio for Thelonious Monk "Thelonious Sphere Monk. October 10, 1917-February 17, 1982. With the arrival Thelonious Sphere Monk, modern music-let alone modern culture--simply hasn't been the same. Recognized as one of the most inventive pianists of any musical genre, Monk achieved a startlingly original sound that even his most devoted followers have been unable to successfully imitate. His musical vision was both ahead of its time and deeply rooted in tradition, spanning the entire history of the music from the "stride" masters of James P. Johnson and Willie "the Lion" Smith to the tonal freedom and kinetics of the "avant garde." And he shares with Edward "Duke" Ellington the distinction of being one of the century's greatest American composers. At the same time, his commitment to originality in all aspects of life-in fashion, in his creative use of language and economy of words, in his biting humor, even in the way he danced away from the piano-has led fans and detractors alike to call him "eccentric," "mad" or even "taciturn." Consequently, Monk has become perhaps the most talked about and least understood artist in the history of jazz. Born on October 10, 1917, in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, Thelonious was only four when his mother and his two siblings, Marion and Thomas, moved to New York City. Unlike other Southern migrants who headed straight to Harlem, the Monks settled on West 63rd Street in the "San Juan Hill" neighborhood of Manhattan, near the Hudson River. His father, Thelonious, Sr., joined the family three years later, but health considerations forced him to return to North Carolina. During his stay, however, he often played the harmonica, 'Jew's harp," and piano-all of which probably influenced his son's unyielding musical interests. Young Monk turned out to be a musical prodigy in addition to a good student and a fine athlete. He studied the trumpet briefly but began exploring the piano at age nine. He was about nine when Marion's piano teacher took Thelonious on as a student. By his early teens, he was playing rent parties, sitting in on organ and piano at a local Baptist church, and was reputed to have won several "amateur hour" competitions at the Apollo Theater. ,Admitted to Peter Stuyvesant, one of the city's best high schools, Monk dropped out at the end of his sophomore year to pursue music and around 1935 took a job as a pianist for a traveling evangelist and faith healer. Returning after two years, he formed his own quartet and played local bars and small clubs until the spring of 1941, when drummer Kenny Clarke hired him as the house pianist at Minton's Playhouse in Harlem. Minton's, legend has it, was where the "bebop revolution" began. The after-hours jam sessions at Minton's, along with similar musical gatherings at Monroe's Uptown House, Dan Wall's Chili Shack, among others, attracted a new generation of musicians brimming with fresh ideas about harmony and rhythm-notably Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Mary Lou Williams, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, Max Roach, Tadd Dameron, and Monk's close friend and fellow pianist, Bud Powell. Monk's harmonic innovations proved fundamental to the development of modern jazz in this period. Anointed by some critics as the "High Priest of Bebop," several of his compositions ("52nd Street Theme," "Round Midnight," "Epistrophy" [co-written with Kenny Clarke and originally titled "Fly Right" and then "Iambic Pentameter"], "I Mean You") were favorites among his contemporaries. Thelonious Monk StyleYet, as much as Monk helped usher in the bebop revolution, he also charted a new course for modern music few were willing to follow. Whereas most pianists of the bebop era played sparse chords in the left hand and emphasized fast, even eighth and sixteenth notes in the right hand, Monk combined an active right hand with an equally active left hand, fusing stride and angular rhythms that utilized the entire keyboard. And in an era when fast, dense, virtuosic solos were the order of the day, Monk was famous for his use of space and silence. In addition to his unique phrasing and economy of notes, Monk would "lay out" pretty regularly, enabling his sidemen to experiment free of the piano's fixed pitches. As a composer, Monk was less interested in writing new melodic lines over popular chord progressions than in creating a whole new architecture for his music, one in which harmony and rhythm melded seamlessly with the melody. "Everything I play is different," Monk once explained, "different melody, different harmony, different structure. Each piece is different from the other. . . . [W]hen the song tells a story, when it gets a certain sound, then it's through . . . completed." ,Despite his contribution to the early development of modern jazz, Monk remained fairly marginal during the 1940s and early 1950s. Besides occasional gigs with bands led by Kenny Clarke, Lucky Millinder, Kermit Scott, and Skippy Williams, in 1944 tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins was the first to hire Monk for a lengthy engagement and the first to record with him. Most critics and many musicians were initially hostile to Monk's sound. Blue Note, then a small record label, was the first to sign him to a contract. Thus, by the time he went into the studio to lead his first recording session in 1947, he was already thirty years old and a veteran of the jazz scene for nearly half of his life. But he knew the scene and during the initial two years with Blue Note had hired musicians whom he believed could deliver. Most were not big names at the time but they proved to be outstanding musicians, including trumpeters Idrees Sulieman and George Taitt; twenty-two year-old Sahib Shihab and seventeen-year-old Danny Quebec West on alto saxophones; Billy Smith on tenor; and bassists Gene Ramey and John Simmons. On some recordings Monk employed veteran Count Basie drummer Rossiere "Shadow" Wilson; on others, the drum seat was held by well-known bopper Art Blakey. His last Blue Note session as a leader in 1952 finds Monk surrounded by an all-star band, including Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Lou Donaldson (alto), "Lucky" Thompson (tenor), Nelson Boyd (bass), and Max Roach (drums). In the end, although all of Monk's Blue Note sides are hailed today as some of his greatest recordings, at the time of their release in the late 1940s and early 1950s, they proved to be a commercial failure. Harsh, ill-informed criticism limited Monk's opportunities to work-opportunities he desperately needed especially after his marriage to Nellie Smith in 1947, and the birth of his son, Thelonious, Jr., in 1949. Monk found work where he could, but he never compromised his musical vision. His already precarious financial situation took a turn for the worse in August of 1951, when he was falsely arrested for narcotics possession, essentially taking the rap for his friend Bud Powell. Deprived of his cabaret card-a police-issued "license" without which jazz musicians could not perform in New York clubs-Monk was denied gigs in his home town for the next six years. Nevertheless, he played neighborhood clubs in Brooklyn-most notably, Tony's Club Grandean, sporadic concerts, took out-of-town gigs, composed new music, and made several trio and ensemble records under the Prestige Label (1952-1954), which included memorable performances with Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, and Milt Jackson. In the fall of1953, he celebrated the birth of his daughter Barbara, and the following summer he crossed the Atlantic for the first time to play the Paris Jazz Festival. During his stay, he recorded his first solo album for Vogue. These recordings would begin to establish Monk as one of the century's most imaginative solo pianists. In 1955, Monk signed with a new label, Riverside, and recorded several outstanding LP's which garnered critical attention, notably Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington, The Unique Thelonious Monk, Brilliant Corners, Monk's Music and his second solo album, Thelonious Monk Alone. In 1957, with the help of his friend and sometime patron, the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, he had finally gotten his cabaret card restored and enjoyed a very long and successful engagement at the Five Spot Café with John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Wilbur Ware and then Ahmed Abdul-Malik on bass, and Shadow Wilson on drums. From that point on, his career began to soar; his collaborations with Johnny Griffin, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey, Clark Terry, Gerry Mulligan, and arranger Hall Overton, among others, were lauded by critics and studied by conservatory students. Monk even led a successful big band at Town Hall in 1959. It was as if jazz audiences had finally caught up to Monk's music. By 1961, Monk had established a more or less permanent quartet consisting of Charlie Rouse on tenor saxophone, John Ore (later Butch Warren and then Larry Gales) on bass, and Frankie Dunlop (later Ben Riley) on drums. He performed with his own big band at Lincoln Center (1963), and at the Monterey Jazz Festival, and the quartet toured Europe in 1961 and Japan in 1963. In 1962, Monk had also signed with Columbia records, one of the biggest labels in the world, and in February of 1964 he became the third jazz musician in history to grace the cover of Time Magazine. However, with fame came the media's growing fascination with Monk's alleged eccentricities. Stories of his behavior on and off the bandstand often overshadowed serious commentary about his music. The media helped invent the mythical Monk-the reclusive, naïve, idiot savant whose musical ideas were supposed to be entirely intuitive rather than the product of intensive study, knowledge and practice. Indeed, his reputation as a recluse (Time called him the "loneliest Monk") reveals just how much Monk had been misunderstood. As his former sideman, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, explained, Monk was somewhat of a homebody: "If Monk isn't working he isn't on the scene. Monk stays home. He goes away and rests." Unlike the popular stereotypes of the jazz musician, Monk was devoted to his family. He appeared at family events, played birthday parties, and wrote playfully complex songs for his children: "Little Rootie Tootie" for his son, "Boo Boo's Birthday" and "Green Chimneys" for his daughter, and a Christmas song titled "A Merrier Christmas." The fact is, the Monk family held together despite long stretches without work, severe money shortages, sustained attacks by critics, grueling road trips, bouts with illness, and the loss of close friends. During the 1960s, Monk scored notable successes with albums such as Criss Cross, Monk's Dream, It's Monk Time, Straight No Chaser, and Underground. But as Columbia/CBS records pursued a younger, rock-oriented audience, Monk and other jazz musicians ceased to be a priority for the label. Monk's final recording with Columbia was a big band session with Oliver Nelson's Orchestra in November of 1968, which turned out to be both an artistic and commercial failure. Columbia's disinterest and Monk's deteriorating health kept the pianist out of the studio. In January of 1970, Charlie Rouse left the band, and two years later Columbia quietly dropped Monk from its roster. For the next few years, Monk accepted fewer engagements and recorded even less. His quartet featured saxophonists Pat Patrick and Paul Jeffrey, and his son Thelonious, Jr., took over on drums in 1971. That same year through 1972, Monk toured widely with the "Giants of Jazz," a kind of bop revival group consisting of Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Al McKibbon and Art Blakey, and made his final public appearance in July of 1976. Physical illness, fatigue, and perhaps sheer creative exhaustion convinced Monk to give up playing altogether. On February 5, 1982, he suffered a stroke and never regained consciousness; twelve days later, on February 17th, he died. Today Thelonious Monk is widely accepted as a genuine master of American music. His compositions constitute the core of jazz repertory and are performed by artists from many different genres. He is the subject of award winning documentaries, biographies and scholarly studies, prime time television tributes, and he even has an Institute created in his name. The Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz was created to promote jazz education and to train and encourage new generations of musicians. It is a fitting tribute to an artist who was always willing to share his musical knowledge with others but expected originality in return."-Robin D. G. Kelley Ph.D. ^ Hide Bio for Thelonious Monk • Show Bio for John Coltrane "John Coltrane, in full John William Coltrane, byname Trane, (born September 23, 1926, Hamlet, North Carolina, U.S.-died July 17, 1967, Huntington, New York), American jazz saxophonist, bandleader, and composer, an iconic figure of 20th-century jazz.John Coltrane, 1966. Coltrane's first musical influence was his father, a tailor and part-time musician. John studied clarinet and alto saxophone as a youth and then moved to Philadelphia in 1943 and continued his studies at the Ornstein School of Music and the Granoff Studios. He was drafted into the navy in 1945 and played alto sax with a navy band until 1946; he switched to tenor saxophone in 1947. During the late 1940s and early '50s, he played in nightclubs and on recordings with such musicians as Eddie ("Cleanhead") Vinson, Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges. Coltrane's first recorded solo can be heard on Gillespie's "We Love to Boogie" (1951). Coltrane came to prominence when he joined Miles Davis's quintet in 1955. His abuse of drugs and alcohol during this period led to unreliability, and Davis fired him in early 1957. He embarked on a six-month stint with Thelonious Monk and began to make recordings under his own name; each undertaking demonstrated a newfound level of technical discipline, as well as increased harmonic and rhythmic sophistication. During this period Coltrane developed what came to be known as his "sheets of sound" approach to improvisation, as described by poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka): "The notes that Trane was playing in the solo became more than just one note following another. The notes came so fast, and with so many overtones and undertones, that they had the effect of a piano player striking chords rapidly but somehow articulating separately each note in the chord, and its vibrating subtones." Or, as Coltrane himself said, "I start in the middle of a sentence and move both directions at once." The cascade of notes during his powerful solos showed his infatuation with chord progressions, culminating in the virtuoso performance of "Giant Steps" (1959). Coltrane's tone on the tenor sax was huge and dark, with clear definition and full body, even in the highest and lowest registers. His vigorous, intense style was original, but traces of his idols Johnny Hodges and Lester Young can be discerned in his legato phrasing and portamento (or, in jazz vernacular, "smearing," in which the instrument glides from note to note with no discernible breaks). From Monk he learned the technique of multiphonics, by which a reed player can produce multiple tones simultaneously by using a relaxed embouchure (i.e., position of the lips, tongue, and teeth), varied pressure, and special fingerings. In the late 1950s, Coltrane used multiphonics for simple harmony effects (as on his 1959 recording of "Harmonique"); in the 1960s, he employed the technique more frequently, in passionate, screeching musical passages. Coltrane returned to Davis's group in 1958, contributing to the "modal phase" albums Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), both considered essential examples of 1950s modern jazz. (Davis at this point was experimenting with modes-i.e., scale patterns other than major and minor.) His work on these recordings was always proficient and often brilliant, though relatively subdued and cautious. After ending his association with Davis in 1960, Coltrane formed his own acclaimed quartet, featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. At this time Coltrane began playing soprano saxophone in addition to tenor. Throughout the early 1960s Coltrane focused on mode-based improvisation in which solos were played atop one- or two-note accompanying figures that were repeated for extended periods of time (typified in his recordings of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things"). At the same time, his study of the musics of India and Africa affected his approach to the soprano sax. These influences, combined with a unique interplay with the drums and the steady vamping of the piano and bass, made the Coltrane quartet one of the most noteworthy jazz groups of the 1960s. Coltrane's wife, Alice (also a jazz musician and composer), played the piano in his band during the last years of his life. During the short period between 1965 and his death in 1967, Coltrane's work expanded into a free, collective (simultaneous) improvisation based on prearranged scales. It was the most radical period of his career, and his avant-garde experiments divided critics and audiences. Coltrane's best-known work spanned a period of only 12 years (1955-67), but, because he recorded prolifically, his musical development is well-documented. His somewhat tentative, relatively melodic early style can be heard on the Davis-led albums recorded for the Prestige and Columbia labels during 1955 and '56. Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane (1957) reveals Coltrane's growth in terms of technique and harmonic sense, an evolution further chronicled on Davis's albums Milestones and Kind of Blue. Most of Coltrane's early solo albums are of a high quality, particularly Blue Train (1957), perhaps the best recorded example of his early hard bop style (see bebop). Recordings from the end of the decade, such as Giant Steps (1959) and My Favorite Things (1960), offer dramatic evidence of his developing virtuosity. Nearly all of the many albums Coltrane recorded during the early 1960s rank as classics; A Love Supreme (1964), a deeply personal album reflecting his religious commitment, is regarded as especially fine work. His final forays into avant-garde and free jazz are represented by Ascension and Meditations (both 1965), as well as several albums released posthumously." ^ Hide Bio for John Coltrane • Show Bio for Coleman Hawkins "Coleman Randolph Hawkins (November 21, 1904 - May 19, 1969), nicknamed "Hawk" and sometimes "Bean", was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. One of the first prominent jazz musicians on his instrument, as Joachim E. Berendt explained: "there were some tenor players before him, but the instrument was not an acknowledged jazz horn". Hawkins biographer John Chilton described the prevalent styles of tenor saxophone solos prior to Hawkins as "mooing" and "rubbery belches". Hawkins denied being first and noted his contemporaries Happy Caldwell, Stump Evans, and Prince Robinson, although he was the first to tailor his method of improvisation to the saxophone rather than imitate the techniques of the clarinet. Hawkins' virtuosic, arpeggiated approach to improvisation, with his characteristic rich, emotional, and vibrato-laden tonal style, was the main influence on a generation of tenor players that included Chu Berry, Charlie Barnet, Tex Beneke, Ben Webster, Vido Musso, Herschel Evans, Buddy Tate, and Don Byas, and through them the later tenormen, Arnett Cobb, Illinois Jacquet, Flip Phillips, Ike Quebec, Al Sears, Paul Gonsalves, and Lucky Thompson. While Hawkins became known with swing music during the big band era, he had a role in the development of bebop in the 1940s. Fellow saxophonist Lester Young, known as the "President of the Tenor Saxophone", commented, in a 1959 interview with The Jazz Review: "As far as I'm concerned, I think Coleman Hawkins was the president, first, right? As far as myself, I think I'm the second one." Miles Davis once said: "When I heard Hawk, I learned to play ballads." " ^ Hide Bio for Coleman Hawkins • Show Bio for Art Blakey "Arthur Blakey (October 11, 1919 - October 16, 1990) was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s. Blakey made a name for himself in the 1940s in the big bands of Fletcher Henderson and Billy Eckstine. He then worked with bebop musicians Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie. In the mid-1950s, Horace Silver and Blakey formed the Jazz Messengers, a group that the drummer was associated with for the next 35 years. The group was formed as a collective of contemporaries, but over the years the band became known as an incubator for young talent, including Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Johnny Griffin, Curtis Fuller, Chuck Mangione, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Cedar Walton, Woody Shaw, Terence Blanchard, and Wynton Marsalis. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz calls the Jazz Messengers "the archetypal hard bop group of the late 50s". Blakey was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame (in 1981). Posthumously, he was inducted into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1991 and the Grammy Hall of Fame (in 1998 and 2001). He was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005." ^ Hide Bio for Art Blakey

12/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

12/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

12/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

12/9/2025

Have a better biography or biography source? Please Contact Us so that we can update this biography.

Track Listing:

1. Monk's Mood 7:48

2. Abide With Me 0:56

3. Well, You Needn't 11:28

4. Ruby, My Dear 5:28

5. Off Minor 5:11

6. Epistrophy 10:48

7. Crepuscule With Nellie 4:40

8. Ruby, My Dear 6:20

9. Trinkle Tinkle 6:41

10. Nutty 6:38

11. Functional 9:44

Hat Art

Improvised Music

Jazz

Melodic and Lyrical Jazz

NY Downtown & Metropolitan Jazz/Improv

Jazz Reissues

Staff Picks & Recommended Items

Hat Hut Masters Sale

Search for other titles on the label:

ezz-thetics by Hat Hut Records Ltd.

![Agnel, Sophie: Learning [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36841.jpg)

![Monaco, Amanda (w/ Michael Attias / Sean Conly / Satoshi Takeishi) : Deathblow [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36956.jpg)

![Frey, Jurg with ensemble]h[iatus: Je Laisse A La Nuit Son Poids D](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36988.jpg)

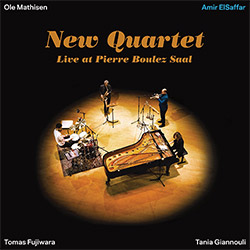

![ElSaffar, Amir / New Quartet : Live at Pierre Boulez Saal [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36830.jpg)

![Zorn, John: The Song of Songs [CD + CD BOOK]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36923.jpg)

![Musicworks Magazine: #152 Fall 25 [MAGAZINE + CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/37004.jpg)

![[ahmed] (Thomas / Grip / Gerbal / Wright): Sama](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36976.jpg)

![Cleaver, Gerald / Brandon Lopez / Hprizm: In The Wilderness [COLOR VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/33060.jpg)

![McPhee, Joe : Defiant Jazz: a Joe McPhee Taster [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36859.jpg)

![Mateen, Sabir / Patrick Holmes / Federico Ughi : Survival Situation [LTD VINYL LP + DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/29891.jpg)

![Tucker, Dave / Pat Thomas / Thurston Moore / Mark Sanders: Educated Guess Vol. 1 [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/30183.jpg)

![Sarian, Michael / Matthew Putman: A Lifeboat (Part I) [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/30426.jpg)

![Carter, Daniel / Tobias Wilner / Djibril Toure / Federico Ughi: New York United Volume 2 [COLOR VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/30665.jpg)

![Mela, Francisco feat. Matthew Shipp / William Parker: Music Frees Our Souls, Vol. 1 [BLUE VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/30999.jpg)

![Heroes Are Gang Leaders: LeAutoRoiOgraphy [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/32253.jpg)

![Carter, Daniel / Matthew Shipp / William Parker / Gerald Cleaver: Welcome Adventure! Vol. 2 [COLOR VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/32385.jpg)

![Carter, Daniel / Evan Strauss / 5-Track / Sheridan Riley: The Uproar In Bursts Of Sound And Silence [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/32515.jpg)

![Ackerley, Jessica / Patrick Shiroishi / Chris Williams / Luke Stewart / Jason Nazary: SSWAN: Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/32586.jpg)

![Mela, Francisco feat. Cooper-Moore / William Parker: Music Frees Our Souls, Vol. 2 [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/32735.jpg)

![Amba, Zoh / William Parker / Francisco Mela: O Life, O Light Vol. 2 [COLOR VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/33059.jpg)

![Dikeman, John / Pat Thomas / John Edwards / Steve Noble: Volume 1 [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/33099.jpg)

![Dikeman, John / Pat Thomas / John Edwards / Steve Noble: Volume 2 [COLOR VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/33184.jpg)

![Genthon, Anouck / Lionel Marchetti: Suite Blanche [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36642.jpg)

![Toeplitz, Kasper T.: Erosions Programmees [CD + BOOKLET]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36639.jpg)

![Gate, The : Amost Live [CASSETTE + MAGAZINE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36836.jpg)

![A Magic Whistle: The Solar Cell [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36658.jpg)

![McGee, Hal: Columbus Expedition [Cassette w/ Download]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36650.jpg)

![Jaeger, Kassel: Fernweh [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36541.jpg)

![+DOG+: The Light Of Our Lives [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36009.jpg)

![Eternities: Rides Again [CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36247.jpg)

![Lopez, Francisco: Untitled (2021-2022) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36438.jpg)

![Frey, Jurg : Composer, Alone [3 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36927.jpg)

![Pisaro-Liu, Michael: Within (2) / Appearance (2) [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36831.jpg)

![Musicworks Magazine: #151 Summer 25 [MAGAZINE + CD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36559.jpg)

![Brown, Dan / Dan Reynolds: Live At The Grange Hall [unauthorized][CASSETTE]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36245.jpg)

![Coultrain: Mundus [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/33056.jpg)

![Hprizm: Signs Remixed [COLORED VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/30635.jpg)

![Halls Of the Machine: All Tribal Dignitaries [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOAD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36134.jpg)

![Koenjihyakkei: Live at Club Goodman [2 CDs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36111.jpg)

![Sorry For Laughing (G. Whitlow / M. Bates / Dave-Id / E. Ka-Spel): Rain Flowers [2 CDS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35985.jpg)

![Rolando, Tommaso / Andy Moor : Biscotti [CASSETTE w/ DOWNLOADS]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/36106.jpg)

![Electric Bird Noise / Derek Roddy: 8-10-22 [CD EP]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35970.jpg)

![Elephant9 : Mythical River [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34624.jpg)

![Elephant9 with Terje Rypdal: Catching Fire [VINYL 2 LPs]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/35355.jpg)

![Deerlady (Obomsawin, Mali / Magdalena Abrego): Greatest Hits [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/34876.jpg)

![Coley, Byron: Dating Tips for Touring Bands [VINYL]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/17906.jpg)

![Lost Kisses: My Life is Sad & Funny [DVD]](https://www.teuthida.com/productImages/misc4/lostKissesDVD.jpg)